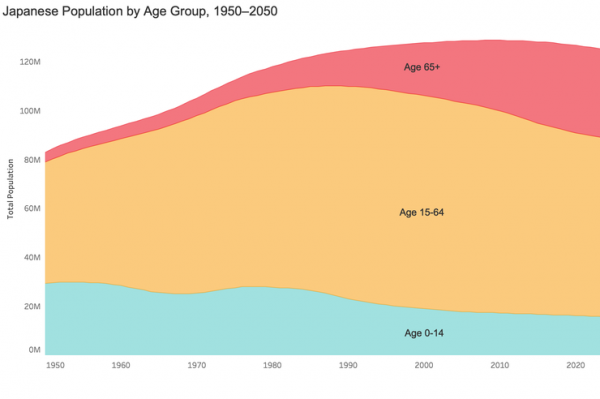

Japan’s long-term care insurance system was launched in April 2000, and in the ensuing years, as domestic demographics have continued to evolve, it has undergone various revisions to meet the changing situation. Currently, the pattern of aging in Japanese society has shifted from a phase in which the actual number of senior citizens was growing rapidly to a phase in which the number is not increasing much, but the relative proportion of those seniors to the overall population is rising as the working-age population is decreasing (see graph below). This phenomenon calls for further changes in the system as it poses the dual challenges of finding new fiscal resources and securing the human resources needed to care for the elderly. Welfare for the elderly in Japan has always and will continue to be a “work in progress,” constantly evolving to keep up with the changing needs.

The first half of this article looks back at the history of welfare for the elderly in Japan and reflects on its shortcomings. It explains the background that led to the creation of the long-term care insurance system, offering insight into the significance of the system and how it developed into what may be considered an optimal solution, the community-based integrated care system.

The article also touches on the launch of the Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative (AHWIN), which offers a different perspective on how Japan and the countries in Asia can work together to tackle the challenges facing aging societies in the coming years in order to create vibrant and healthy societies where people can enjoy long and productive lives.

The author hopes that this article delineating the experiences of Japan, which was a forerunner in Asia in terms of becoming an aging society, will offer some insight and hints for the other countries in the region that will soon be undergoing rapid aging as well. It is also important for Japan to open up and reach out to other countries in Asia and the world to gain a broader perspective, one that may lead to new clues and solutions in tackling the aging issue.

The Development of the Health and Welfare System for the Elderly in Japan

The Evolution of the Social Welfare System in Postwar Japan

The scale of social security benefits in Japan reached ¥121.3 trillion in fiscal year (FY) 2018 or 21.5 percent of GDP. The breakdown is about 50 percent for pensions, 30 percent for medical subsidies, and 20 percent for welfare, which includes long-term care for the elderly.

Social security in Japan began in 1945, as part of the postwar recovery efforts, and it expanded along with the high economic growth enjoyed from the 1960s onward. The framework for the social security system took form as Japan succeeded in enrolling all its citizens in public health insurance and public pension plans, achieving “universal health and pension coverage” in 1961.

The initial challenge was to raise the payments, which had been set too low. In 1973, just before the first oil crisis, the payment levels were substantially raised, and that reform resulted in the rapid expansion of Japan’s social security system.

In the early 1980s, as Japan braced for the full-fledged greying of its society, the focus turned to “rethinking welfare,” and a series of reforms were introduced to address the impact of the aging population and the changing industrial structure on pensions and medical care. The expansion of social security during the 1980s paralleled the country’s economic growth and showed a stable upward trend.

However, with the start of the 1990s, the bubble economy collapsed and the Japanese economy entered a long recession. During the period from 1990 to 2016, while Japan’s GDP grew 18.2 percent, rising from ¥451.6 trillion in 1990 to ¥539.2 trillion in 2016, social security expenditures rose 246 percent, leaping from ¥47.4 trillion to ¥116.9 trillion. As a result, from the latter half of the 1990s through today, Japan has been making efforts to ensure the sustainability of the social security system.

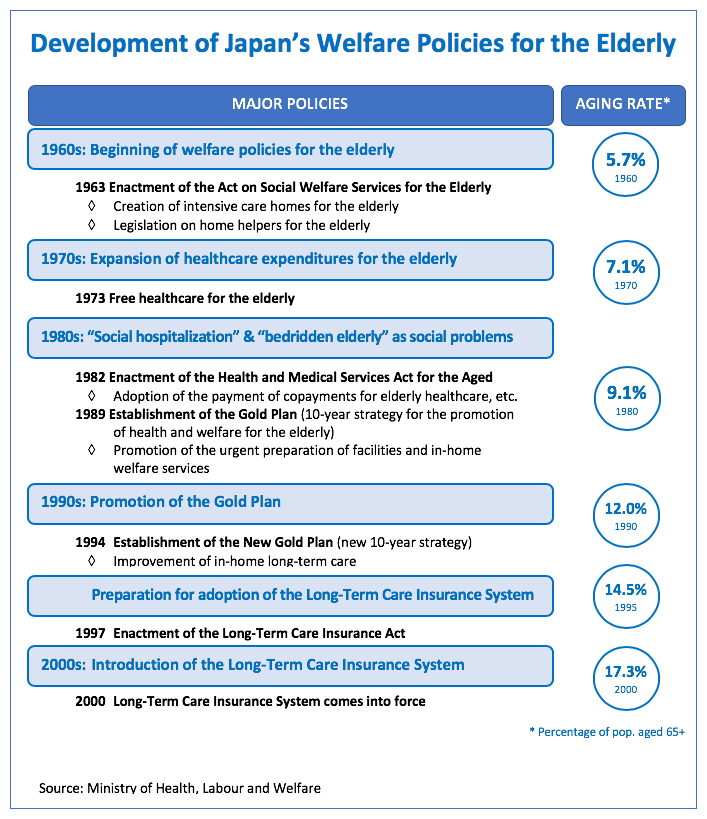

During this same period, the aging of Japan’s population continued to advance. The average life expectancy of the Japanese in 1960 was 65.32 years for men and 70.19 years for women, and people aged 65 or older represented 5.7 percent of the country’s total population. In 2017, life expectancy had risen to 81.09 years and 87.26 years respectively, while the percentage of seniors in the population had risen to 27.7 percent. Japan became an “aging society” when the percentage of seniors reached 7 percent in 1970, and an “aged society” upon reaching the 14 percent level in 1994.

Public assistance for long-term care for the elderly began to be carried out as “welfare” under the Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly, which was enacted in 1963. However, once the Long-Term Care Insurance Actcame into effect in 2000, care for the elderly was incorporated into the social insurance system.

The Beginning of Social Welfare for the Elderly: Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly and the Health and Medical Services Act for the Aged

Welfare provisions for the elderly in Japan date back to 1963, when the Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly was introduced. Of course, the “elderly issue” existed long before this act was implemented, but at that time it was generally thought that family members should be responsible for taking care of their elderly kin, and so a high percentage of the elderly in Japan lived with their families.Older persons in need of assistance were considered “low-income seniors without close family members to support them.” Thus, “nursing homes” (yoro shisetsu) under the public assistance system were considered to be outlets for those older persons who were exceptions to the rule.

The Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly continued to support public assistance–based nursing facilities as “nursing homes for the elderly” (yogo rojin hoomu) and also established intensive care homes for the elderly” (tokubetsu yogo rojin hoomu, or “tokuyo”) in response to the need to provide for those elderly people in need of constant care. At the time this law was enacted, there was only one such intensive care home for the elderly in existence in Japan, and thus this law was in fact the country’s first step on the path toward long-term care for the elderly.

Incidentally, in 1963, the government of Japan also introduced a special program to reward people over the age of 100. When the program started that year, there were just 153 persons over the age of 100. That number grew to 679,785 in 2018, demonstrating just how striking the increase in life expectancy in Japan has been in a matter of half a century.

Against that backdrop, it would not be an overstatement to say that policies developed under the Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly were almost entirely dedicated to creating intensive care homes for the elderly. By 1980—17 years after the law was enacted—there were 1,031 intensive care homes for the elderly and now the number has grown to approximately 9,700 throughout Japan.

In 1973, Japan decided to offer free healthcare for the elderly. However, that policy led to a steep rise in medical expenses for the elderly and placed an enormous financial burden on the national health insurance budget. As a result, 10 years later, in 1983, the Health and Medical Services Act for the Aged was introduced, abolishing free healthcare for the elderly and requiring the elderly to pay a modest copayment.

The Health and Medical Services Act for the Aged also played an important role in terms of long-term care. Not only did this law create a system to share the burden of medical expenses for those aged 70 and up among all of the medical insurance systems, but it also prescribed consistent health and medical services from prevention to rehabilitation. It was owing to this legislation that municipalities started offering medical check-ups for the elderly. With the revision of the act in 1987, health facilities for the aged (rojin hoken shisetsu, or roken) were established as intermediary facilities to take care of the elderly between being hospitalized and staying at home; these were intended to complement the already existing intensive care home for the elderly (tokuyo). A further revision of the act in 1991 introduced the visiting nursing system.

In the area of welfare services for the elderly, from the 1980s, day services and short-stay services were incorporated into the national budget system. When the national subsidy for residential care facilities was cut from 80 percent down to 50 percent in the late 1980s, in-home services were also allocated a 50 percent subsidy under the Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly. The next challenge was to strengthen these three pillars of in-home services, namely, home help services, day services, and short-stay services.

Toward Consolidation of Long-Term Care in 2000: The Gold Plan and the Revision of the Eight Welfare-Related Acts

In April 1989, Japan introduced a new consumption tax, which led to the argument that the use of the additional revenue should be used to enhance public welfare. During the budget compilation at the end of 1989, a Ten-Year Strategy to Promote Health and Welfare for the Aged—known as the “Gold Plan”—was formulated to set up the infrastructure necessary to provide health and welfare services for the elderly by 2000.

The Gold Plan was ground-breaking in that (1) it was a long-term (10 years) plan rather than the single-year budgeting that had been the norm in the welfare field; (2) it set clear numerical targets (i.e., 100,000 home helpers, 50,000 beds for short stays, 10,000 facilities for day services, 240,000 beds in intensive care homes for the elderly, etc.); and (3) it placed top priority on urgently preparing to provide in-home welfare services.

In order to pave the way for the implementation of the Gold Plan, in 1990 eight welfare-related acts were amended, including the Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly. The main substance of the revision can be summarized as follows: (1) it provided a clear definition of in-home welfare services in all of the acts and placed priority on in-home welfare services to support independent living by the elderly; (2) it transferred the management of residential facilities from prefectures to local municipalities in order to establish a structure that provides integrated and comprehensive welfare services both in homes and in care facilities; and (3) it required that municipalities formulate health and welfare plans for the elderly to systematically promote health and welfare measures. Through these amendments, plans were established to create a foundation for long-term care at the municipal level throughout the country, and in 1995, building on that, a “New Gold Plan” was introduced that upwardly revised the targets to be achieved by the year 2000.

Problems with Social Welfare for the Elderly Prior to 2000

Before the creation of the long-term care insurance system, there were many shortfalls in Japan’s health and welfare provisions for the elderly. Roughly speaking, the main problems can be broken down into the following areas:

a. The authority to make decisions on permissible usage of services was an issue. Municipal governments had the right to decide on the placement of elderly persons in facilities such as intensive care homes for the elderly. Similarly, the government was in charge of determining the services that could be used, and the users themselves could not directly communicate with service providers to decide on the services to be rendered.

b. Maintenance of care facilities relied on subsidies from the national and municipal governments and were therefore limited within that budget.

c. The user contribution (copayment) for services was dependent on their ability to pay. While those with low incomes might be exempt from copayments or be charged a very low fee, for those in the middle to upper income groups, the copayments could be quite high, and in some cases, the user was expected to cover the entire amount. Accordingly, the copayments posed a high financial burden for the middle-income group.

d. Medical expenses for the elderly became free in 1973, and even after copayments were reintroduced under the Health and Medical Services Act for the Aged in 1983, the amount was a small fixed fee. This made it less expensive for middle-class seniors to be hospitalized than to be admitted at an intensive care home for the elderly. For that reason, there was a tendency among this group to excessively rely on hospitalization.

e. Because “nursing homes” were considered facilities for those requiring public assistance before the introduction of welfare for the elderly, it was extremely difficult to erase the stigma that equated welfare with poverty, and so those in the middle class refrained from utilizing welfare services.

f. The municipal governments that were tasked with management decisions (usage decisions) also shared the accepted notion of welfare as being for the poor and tended to consider care facilities solely to accommodate low-income individuals.

Under the system for service providers, intensive care homes for the elderly could only be established by public agencies or social welfare corporations and home helpers were either civil servants or helpers from municipal social welfare councils. By the end of the 1980s, there were calls for greater diversification of service providers and there was some easing of the regulations to allow municipalities to outsource some of the home helper services to silver service business operators. In addition, the existing service providers were joined by various cooperative associations like the co-ops and agricultural cooperatives, municipal quasi-governmental welfare authorities (fukushi kosha), and NGOs and other organizations, all of which vigorously worked to develop the field of elderly care.

The Gold Plan and the revision of the eight welfare-related acts greatly contributed to building the basic infrastructure for long-term care for the elderly. Even under the previous government-run system of long-term care, starting from 1990, counseling and support mechanisms were added through in-home care support centers and other locations that were as near to the users as possible with the goal of offering user-friendly welfare services. However, the amount of services to be offered was basically decided based on the “needs” envisioned by the government, and those needs were limited to low-income individuals, so they did not provide services that were easily accessible to the broader middle class. In order to respond appropriately to the long-term care needs of the broader population, a radical reform was needed, and thus began the drafting of a new “welfare vision” and the creation of the long-term care insurance system.

The Creation of the Long-Term Care Insurance System

From the mid-1990s, discussions unfolded in preparation for establishing a long-term care insurance system. After much deliberation in government council meetings, within the ruling party, and in the Diet, the Long-Term Care Insurance Act was passed in December 1997 and was enacted in April 2000.

In the history of Japanese social security, the long-term care insurance system was the first new insurance system to be introduced since the country’s successful establishment of universal health and pension coverage. Since only a handful of countries (e.g., Germany) have any insurance system for the long-term care of the elderly, there were not many examples from which those involved in the creation of the new system could learn, and so smoothly implementing this system was viewed as a major challenge.

In particular, the municipalities, which had been appointed as the insurers after much debate, faced a wide range of questions, including whether they could actually collect premiums and whether they could offer long-term care services that would meet the expectations of their residents. Each municipality gathered personnel and set up a new division to oversee long-term care, undertaking preparations that included efforts like informational meetings for local residents to explain the new system. Likewise, service providers faced this new system with many concerns and expectations. They wondered if they could make the shift smoothly from the old system, under which they were commissioned by the government and operated their programs with “placement fees,” to the new long-term care insurance system based on user choice and operating with “long-term care fees.”

The significance of the establishment of the long-term care insurance system can be summarized as follows:

From Government Placement to User Selection

The introduction of the long-term care insurance system was in fact a paradigm shift from a system in which seniors received whatever services were approved and assigned by the government to one in which they were able to choose and contract the services themselves.

The new system was to be “user-oriented,” and the emphasis was on the fact that seniors could receive integrated health, medical, and welfare services from diverse agents “based on their own choice” rather than being “assigned” by the municipal authorities. Naturally, problems arose in terms of how to handle cases where the user did not have the capacity to make their own decisions. To address that problem, the “adult guardianship system” was introduced at the same time, starting in April 2000. The two systems were considered to be interdependent and essential to the effective provision of welfare for the elderly.

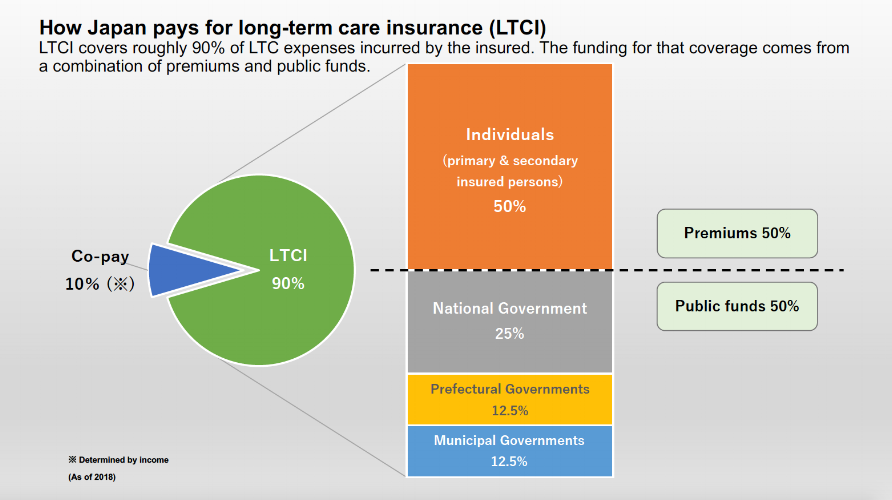

From a Tax-Based Welfare System to an Insurance-Based System

The long-term care insurance system, as the name indicates, adopted the insurance method for addressing long-term care. Everyone over the age of 40 is to be insured and they are divided into two age groups: those aged 65 and over are “primary insured persons,” while those between the ages of 40 and 64 are deemed “secondary insured persons.” The premiums paid by those insured persons are to cover half the funding for the system. The ratio of the premiums for the primary and secondary insured persons is determined based on the populations of the two age groups in order to have flexibility to adapt to the aging populace. The remaining half of the benefits is to be provided by the national, prefectural,and municipal governments from tax revenues at a ratio of 2:1:1. The municipalities serve as the insurers. As a rule, service users are to cover 10 percent of the long-term care services they utilize.

In this way, long-term insurance became a system operated through cost-sharing, where all involved in the system help finance services by paying both a premium and user fees. Moreover, precisely because everyone in Japan pays those premiums and fees, the previous perception that benefits for the elderly were a form of benevolence for the poor was replaced by a strong sense that everyone has the right to use those services. That, in turn, led to a dramatic broadening of the scope of users to include citizens of all economic levels.

Decentralized System Linking Benefits and Burdens

Under the long-term care insurance system, the insurers are the municipalities and they come up with long-term care plans in three-year cycles, together with the premium to be charged in order to cover the costs of the plan. Since, as noted above, 50 percent of the funding of the insurance derives from public funds and 50 percent from premiums, each municipality sets its own standards for the premium to be paid by the primary insured persons.

The higher the amount of benefits offered, the higher the premiums become for citizens aged 65 and over and the higher the tax burden that the municipalities must bear. In other words, the benefits and burdens are closely linked to one another.

Because the kinds of services offered by the municipality to its residents determines its premium level, municipalities must consider both sides of the equation as they manage the long-term care insurance system. Having been devised in this way, Japan’s long-term care insurance is very much a decentralized system, in contrast to the traditional welfare and medical insurance systems.

Integration of Medical Treatment and Welfare

The importance of coordinated medical and welfare systems is a well-recognized issue in elder care and is considered to be a challenge by all stakeholders. The long-term care insurance system aims to integrate medical and welfare services by bringing together all such services previously offered under the Act on Social Welfare for the Elderly and the Health and Medical Services Act for the Aged under its system.

In terms of the types of facility-based services offered, the new system added long-term care health facilities and dedicated medical long-term care sanatoriums to the existing intensive care home for the elderly. As for in-home services, in addition to the three previous pillars (home help, day service, and short-stay admission), new services also came under the insurance coverage such as guidance for management of in-home medical long-term care, home-visit nursing, and outpatient rehabilitation. Other new services incorporated under the insurance coverage included small group homes for people with dementia and the rental of equipment for long-term care covered by public aid.

Introduction of a New Procedure for Determining Benefits—Certification of Needed Long-Term Care and Care Plans

What kind of benefits are given to which users is one of the most important aspects in formulating a social security system. The long-term care insurance system as a rule offers long-term care services to those aged 65 and older who require it, but it stipulates that they must first be screened to receive “certification” of that need. More specifically, the standards for certification fall into seven categories: two different levels for those in need of support and five for those in need of long-term care. Those wishing to utilize services must first apply to the municipality for screening, which is conducted based on nationally established certification standards. The extent of services that the senior can access is decided based on their “certified” level of need, and for those applying for in-home services, an upper limit is set, above which the user must bear the full cost of the extra services received. A care plan is made for the provision of services, and a new category of workers was created called “certified care managers,” who are trained specialists in creating and managing care plans.

Thus, the long-term care insurance system was innovative since as the system shifted from a placement-based system where the use of services was decided by the local government to a system based on user selection of services, and a new process was introduced to determine benefits.

The Impact of the Introduction of the Long-Term Care Insurance System

With the implementation of the long-term care insurance system, access to long-term care services for the elderly became universal and the number of care recipients and quantity of services offered increased dramatically. The number of people certified as eligible for long-term care in FY2000 was 2.18 million; in FY2008, the total increased to 4.55 million, and by FY2018, it had reached 6.33 million.

In parallel to the increase in the number of benefit recipients and the amount of services offered, total expenditures for long-term care tripled from ¥3.6 trillion in FY2000 to ¥11.1 trillion in FY2018. This inevitably resulted in a rise in the premium for long-term care insurance. While the premium charged in FY2000 was ¥2,911 per month per person, in FY2018 it had increased to ¥5,869 per month.

The steady growth in services offered through the long-term care insurance system testifies to the support from the public for the user-oriented, contract-based system that is much more convenient than the former placement-based system where the municipal government decided on all matters concerning long-term care. At the same time, if it were not for the efforts of the municipalities and other stakeholders in the long-term care service sector to ensure that proper services are offered, Japan might have ended up “with insurance, but without services.”

The Impact of the Introduction of the Long-Term Care Insurance System

With the implementation of the long-term care insurance system, access to long-term care services for the elderly became universal and the number of care recipients and quantity of services offered increased dramatically. The number of people certified as eligible for long-term care in FY2000 was 2.18 million; in FY2008, the total increased to 4.55 million, and by FY2018, it had reached 6.33 million.

In parallel to the increase in the number of benefit recipients and the amount of services offered, total expenditures for long-term care tripled from ¥3.6 trillion in FY2000 to ¥11.1 trillion in FY2018. This inevitably resulted in a rise in the premium for long-term care insurance. While the premium charged in FY2000 was ¥2,911 per month per person, in FY2018 it had increased to ¥5,869 per month.

The steady growth in services offered through the long-term care insurance system testifies to the support from the public for the user-oriented, contract-based system that is much more convenient than the former placement-based system where the municipal government decided on all matters concerning long-term care. At the same time, if it were not for the efforts of the municipalities and other stakeholders in the long-term care service sector to ensure that proper services are offered, Japan might have ended up “with insurance, but without services.”

The Ongoing Evolution of the Long-Term Care Insurance System

One of the conditions stipulated when the long-term care insurance system was established was that the content was to be reviewed five years after enactment of the law, with the understanding that issues that had been left unresolved or had been raised for discussion when the system was created would be revisited. In the revision of 2005, measures were reviewed in order to fully enforce the principles delineated in the Long-Term Care Insurance Act while also addressing new challenges that had become evident once the law began to be implemented. These included, for example, (i) a surge in the number of people certified as eligible for long-term care, especially those with lower levels of care requirement; (ii) the weakness of in-home service; (iii) an increase in the use of residential services; (iv) the state of care management; and (v) and demand for dementia care.

Instead of a simple either-or choice between facility- or home-based care, a new service system was suggested that would offer a “new place to live” instead of one’s home and “community-based, small-scale multi-functional care.” Furthermore, for those in need of lower levels of care, greater emphasis was placed on rehabilitation, and the concept of “long-term care prevention” was introduced. Thus, measures are constantly being developed to meet the changing needs.

The Future of the Social Security System

As can be seen from the discussion above, Japan has made great advances since 2000 in terms of elder care, but from an economic standpoint, this period coincides with Japan’s so-called “lost decades”—a 20-year period of recession that followed the bursting of the economic bubble in 1990. A curtailment of pension and medical benefits and other systemic reforms were made to Japan’s social security system. Yet long-term care for the elderly witnessed exceptionally positive development. The reason for that is that when Japan introduced a consumption tax in 1989, there was a strong negative reaction from the public, and the government subsequently sought to implement some policy that would appease its citizens; as Japan was starting to see an escalation in the aging of its population, the government decided to focus on adopting measures to further enhance care for the elderly.

Currently, Japan’s social security budget accounts for more than half of the country’s general expenditures and continues to grow, so finding a way to cover these costs is a major challenge on the domestic political front. From the demographic viewpoint, the overall population in Japan began to decline from 2008 on, while the number of those aged 65 and over is expected to continue to grow until 2042. As more people enter the “oldest-old” age group and the number of those certified to be in need of care increases, the content of medical services required will become more serious and demanding, which will require the establishment of a system that provides seamless medical and long-term care services. To meet such long-term care needs, Japan has put forth a policy objective at the national level of creating an “integrated community care system,” which is being promoted nationwide. This system would allow the elderly—even when they reach the stage where they need more substantial care—to live out their entire lives in their own community by providing for housing, healthcare, long-term care, prevention, and living support in an integrated manner.

The Launch of the Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative (AHWIN)

According to UN demographic projections, many Asian countries will be experiencing rapid aging—at a much faster speed than Japan—and will become aging societies in the near future. Aging is therefore becoming a common challenge for all of Asia.

In 2016, the government of Japan announced the launch of its Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative (AHWIN), calling for joint efforts by Japan and its Asian neighbors to work together with the goals of creating a vibrant and healthy society where people can enjoy long and productive lives and contributing to sustainable economic growth in the region. In July 2016, the basic principles of the initiative were decided and a Private Sector Consortium of the Asia Health and Wellbeing Initiative was set up to promote the initiative in the private sector. This author was appointed as the first chairman of that consortium.

Members of the consortiuminclude representatives from the government of Japan and from approximately 400 domestic medical and long-term care organizations and businesses, private companies involved in elderly-related fields, and others. Preparations are underway for sharing Japan’s knowledge and experience in the field of aging with relevant actors in Asia. Discussions to date have focused in particular on (i) introducing technologies related to elder care that can be useful to other Asian countries, (ii) creating a training and education system to accept care workers from Asia, and (iii) supporting the promotion of the Japanese care industry in other Asian countries. The results of the discussions and measures adopted will be introduced through the AHWIN website.

Conclusion

It is hoped that this article will be of assistance to readers elsewhere in Asia as they work to create new welfare-related systems for the elderly and promote industries focused on the needs of the elderly. Likewise, it is hoped that the introduction of AHWIN through its website will lead to greater understanding of its principles and will enhance cooperation between Japan and its neighboring countries to develop a sustainable framework for providing social care for the elderly. It is this author’s firm belief that stronger ties forged between Japan and the Asian community will help lead to breakthroughs in tackling the numerous challenges our societies all face.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Shuichi Nakamura has been a key actor in the development of Japan’s long-term care system. A graduate of the University of Tokyo majoring in law, Shuichi Nakamura joined the then Ministry of Health and Welfare in 1973. His first assignment was with the Division of Social Welfare for the Elderly in the Social Bureau. He was then seconded to the Japanese Embassy in Sweden, which was followed by an assignment with the Hokkaido Prefectural Government before returning to the ministry. Mr. Nakamura has since served as director of the Division of Social Welfare for the Elderly, Pension Division, Policy Planning Division of the Health Insurance Bureau, and Policy Division of the Minister’s Secretariat in the former Ministry of Health and Welfare. When the ministry assumed its current name of Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, he was appointed deputy director general of the Minister’s Secretariat, then director general of the Health and Welfare Bureau for the Elderly, and next of the Social Welfare and War Victims’ Relief Bureau. He retired from the ministry in 2008 and became head of the Health Insurance Claims Review & Reimbursement Services. From October 2010 to February 2014, Mr. Nakamura served as the secretariat and leader of the team on social security reform deliberations within the Cabinet Secretariat, supervising a series of integrated reforms of the social security and taxation system. In addition to chairing the Private Sector Consortium of AHWIN, he currently serves as president of the Forum for Social Security Policies and as vice chancellor of the Graduate School of the International University of Health and Welfare.